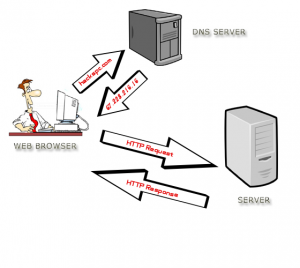

DNS or Domain Name System is a key ingredient in making sure humans can easily access the internet. Without it, internet browsers would have a painfully hard time retrieving web pages at your request. Basically, it resolves domain names to numbers (IP addresses) in the same manner that you assign names to phone numbers.

Why is DNS used?

Computers don’t communicate in the same way as humans. They use numbers to “talk” to each other instead of languages. A third party is needed to overcome the language barrier. This is where DNS comes in.

DNS is commonly seen as an internet phone book. It stores IP addresses, which you retrieve by typing a domain name (i.e. www.rootleveltech.com) in your web browser. However, there’s more to the process than simply matching names to numbers.

How does it work?

Let’s say you need to access Wikipedia for research purposes. Once you type “www.wikipedia.org” in the address bar and hit Enter, your computer’s first order of business is checking its own cache memory to see if it already has the IP address for Wikipedia stored. If you live in a household with at least one high school student, your computer’s cache memory most likely already has Wikipedia’s IP address. But for the purpose of this post, let’s assume it’s otherwise.

After your computer finds out that it has no record of Wikipedia’s IP address, it will send a request to the so-called “resolver,” which is a DNS server typically handled by your Internet Service Provider (ISP). The resolver will then check its own cache memory for Wikipedia’s IP address. Again, let’s assume the resolver doesn’t have the info.

In the event that your ISP’s DNS server is malfunctioning, you can also use third-party DNS servers like Google Public DNS and OpenDNS.

A game of hot potato

The resolver will then send another request to the “root server,” which sits at the top of the DNS hierarchy. Root servers are hundreds of networked servers scattered around the world, grouped into 13 and governed by 12 different organizations. You can check out the 12 organizations at the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA).

Now, a root server’s job isn’t to supply Wikipedia’s IP address. No, its job is to point the resolver in the right direction. More specifically, in the direction of the “top-level domain” where Wikipedia is under. That would be the .org top-level domain.

There are numerous existing top-level domains, such as .com, .net, and country specific ones like .jp (Japan), .au (Australia), and .de (Germany). Once the top-level domain receives the resolver’s request, it will redirect to the “Authoritative Nameserver” where all the domain data is actually stored. This includes all the IP addresses.

The final leg

Finally, the Authoritative Nameserver will tell the resolver Wikipedia’s IP address, which will be used to display the Wikipedia web page in your browser. The resolver will also store Wikipedia’s IP address in its cache memory. This will make the process much faster for similar requests in the future.

That’s how DNS works, everyone. We hope we were able to help you understand what goes on behind the scenes every time you try to access a website.

Have any questions? Need assistance? Contact us!